Interview: Agata Wozniak-Kwasniewska, Aerial Photographer

Photographer: Agata Wozniak-Kwasniewska

Based: Norway

Instagram: @agatawk_photo

“Aerial photography opens up a completely new world, new emotions, new possibilities, that was once reserved only for pilots. One of my most memorable early moments was flying over a snowy forest while floating clouds slowly revealed the landscape. I was so awestruck that I forgot to press the record button…”

Aerial Perspectives

1. What first inspired you to try aerial photography, and do you remember your first flight or image that made you realise the creative potential of drones?

Since I was a little girl, I was always drawn to elevated perspectives, I’d climb the highest tree or hill in sight. As a young adult, I got into climbing and hiking more seriously. And yes, I always chose the window seat on the plane, not just because of motion sickness!

When drones became more accessible to regular users, I admired others’ work from afar, as I couldn’t afford one at the time. In December 2022, I finally gifted myself a Mini 3 Pro for my 40th birthday. And guess what—I crashed it into a tree during my very first flight. I was using MasterShots without realizing how much open space it needs. Luckily, the drone survived its encounter with a Norwegian pine tree and landed safely in a snow pile.

The learning curve with the joystick was long and painful. I’ve never played video games, so controlling a drone felt very unintuitive at first. I flew the wrong way, turned the wrong direction, made all the classic mistakes. It took six months and at least three flights per week, regardless of the weather (I live in Norway, so winter flying meant frozen fingers), to finally feel comfortable.

Long story short: from the very first flight, I knew why I had wanted to do this for so long. Aerial photography opens up a completely new world, new emotions, new possibilities, that was once reserved only for pilots. One of my most memorable early moments was flying over a snowy forest while floating clouds slowly revealed the landscape. I was so awestruck that I forgot to press the record button… Just one more thing on my long list of drone-related fails :)

2. You’ve photographed some incredible mountain regions with your drone. How does the experience of flying and shooting in the mountains differ from coastal or urban/other locations?

It depends heavily on the environment.

I personally don’t fly in cities as it’s heavily restricted where I live, and frankly, urban locations don’t really inspire me. Flying in the mountains, however, is an incredible experience - but also much riskier. You can’t rely on what you feel standing still; even if there’s no wind at your location, your drone can get hit by sudden gusts the moment it crosses a ridge or exits a valley.

Coastal areas are easier in general because they’re more open and flat, unless you’re in places like Lofoten or northern Norway, where mountains drop straight into the sea. Those flights combine the risks of both.

“Honestly, I’ve learned that 70% of the time conditions might be boring, but you’ll never know unless you go out. So I go.”

3. Can you describe a memorable or challenging moment from flying your drone in places like Norway or Iceland? Was there ever a flight you’ll never forget?

Oh yes, actually two that gave me minor heart attacks!

The first one was in Lofoten last year. I wanted to photograph Roren, which was partially covered in clouds. But since that area belongs to Lofotodden National Park, where drone flights are strictly prohibited, I had to launch from far out at sea to legally stay outside the park boundaries. That meant flying nearly 3 km one way… against the wind.

I waited until midnight when the light from the midnight sun lit the ridge perfectly, then sent my drone. The return flight was intense. I had just enough battery to shoot and fly back, and my drone returned with only 10% left. I got the shot, but I was a nervous wreck afterwards.

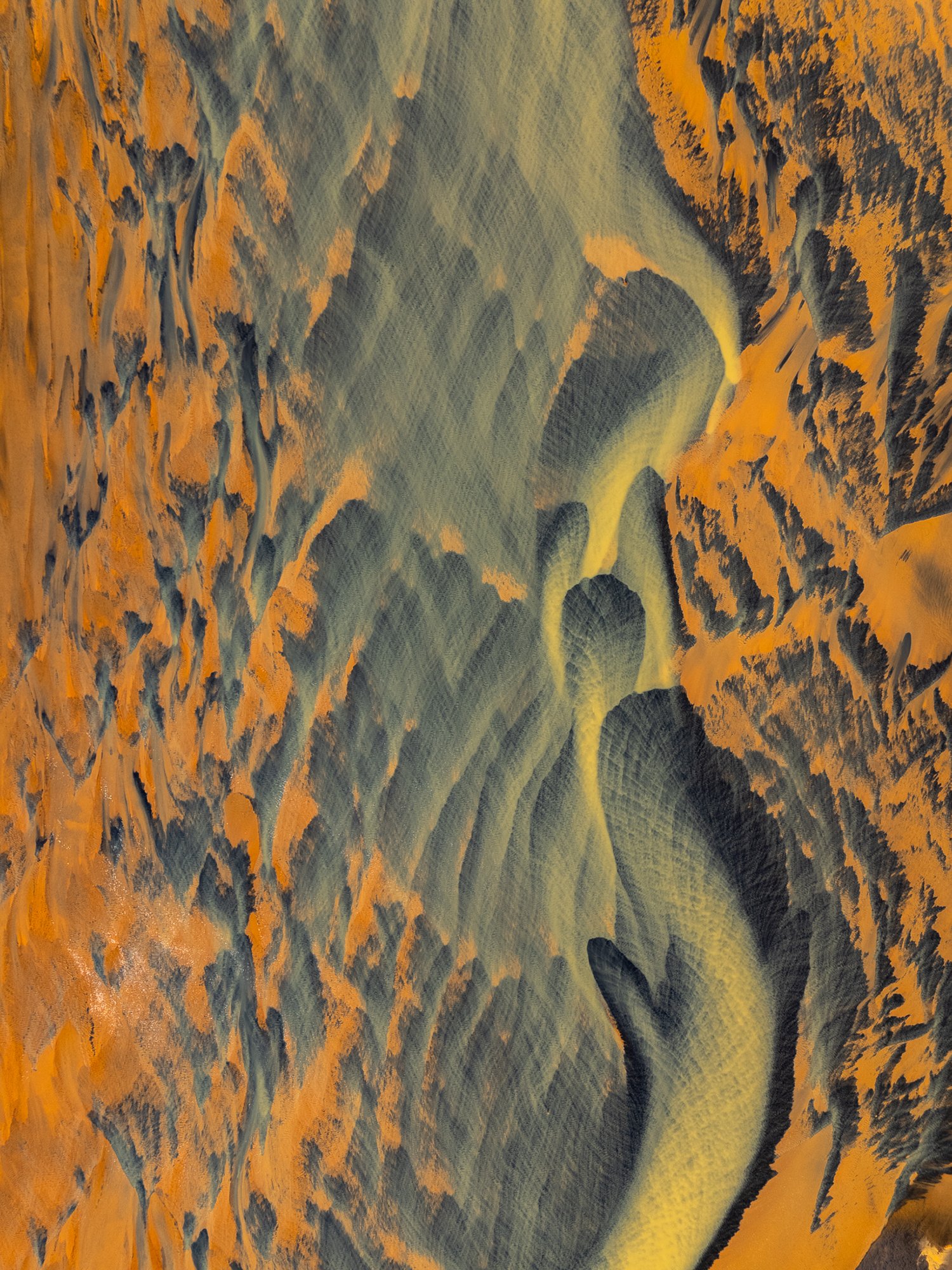

The second was in Iceland a few weeks ago. I flew to capture the river mixing with the ocean, about 1.5 km away. But I got so distracted by the amazing patterns along the way that by the time I reached the main location, I had only 30% battery left. And if you’ve ever flown in Iceland, you know it’s windy, so forget about the advertised 46 minutes of flight time.

On the way back, the drone initiated automatic landing… right over the river! My heart rate was through the roof. I fought the sticks, pushing it forward and upward to get it out of the water zone. If it landed in the fields, I could walk to it. But the river? Disaster—especially on the first day of our trip. I still can’t believe I managed to bring it back safely. Took me a solid 30 minutes to calm down.

What did I learn? Control under pressure. Would I do it again? …Yes 😅 But only because I know my drone and I had wind on my side. It would’ve ended very differently otherwise. So please, don’t try this if you’re just starting out.

4. What are your favourite conditions for drone photography, do you have a preferred time of day or season that produces the most inspiring results?

I love flying when it’s cloudy, especially when low clouds drift through forests or wrap around mountain ridges. There’s something mystical about those slow reveals. Sunrises have always been my favorite time to shoot. The light is softer, the air is fresh, and in popular spots, it’s blissfully quiet. Plus, there’s often fog in the valleys.

In the region of Norway where I live, autumn and early winter are magical. The moisture in the air creates dramatic fog and low clouds, and the first snowfalls highlight the landscape without covering everything. I’ve also flown in -25°C through stunning clouds—and while it’s painful on the hands, it’s often worth it.

Honestly, I’ve learned that 70% of the time conditions might be boring, but you’ll never know unless you go out. So I go.

5. Safety and rules are so important for drone pilots. What’s your approach to researching local regulations and respecting nature when travelling to new destinations?

That’s a hugely important topic.

Social media is full of drone shots from places where flying is strictly prohibited, unless you have scientific permits. Look at places like Kvalvika Beach or Ryten in Lofoten. Værøy even has a helicopter landing zone. On top of that, once the no-fly zone ends, you’re often inside a protected nature reserve. Still, influencers fly there all the time, and it drives me mad. There’s so much disrespect.

Iceland is another good example. Most popular tourist locations are off-limits for drones, for good reasons, like visitor safety. Yet people still launch right over crowds. It’s not hard to research the rules when you travel. Yes, it takes time, but you're not alone in those landscapes.

During my last Iceland trip, the drone permit window was from June 15 to September 15. By chance, we were there right before the restriction period, so I was able to fly legally in some amazing places. I still emailed the Icelandic Environmental Agency just to double-check I understood everything correctly. They were incredibly helpful. If you’re ever unsure, ask.

Another issue is mini drone users, who often skip any kind of training. Many of them don’t know the rules, and that ignorance adds to the increasing bans we’re seeing worldwide.

So, please, do your research. Check drone maps and apps. Norway has excellent tools that show restricted zones and even your live location in relation to park boundaries. It only takes a few minutes.

6. What features or settings do you use most often on your drone, and do you have any technical tips for capturing sharper, more creative images in rugged environments?

With my DJI Air 3, I rely a lot on its dual camera system, especially the medium tele lens, which lets me isolate interesting shapes in the landscape or compress layers for a more dramatic effect. I always use manual exposure settings and keep the histogram visible during flight to avoid overexposing highlights, especially in snow, sand, or bright skies. When the landscape has a lot of contrast, I use bracketing, five shots if needed, or three when the light is more balanced. Shooting in RAW is a must for me—I want full control in post, especially when working with subtle tones like fog or dusk light.

For sharper images in rugged conditions, I usually increase shutter speed to at least 1/250s if there’s any wind. I also turn off obstacle avoidance when I need smooth tracking shots close to cliffs or terrain, it gives me more precise control. But that can be dangerous, so don’t do it unless you’re fully confident with your drone. ND filters are also essential when I want to maintain cinematic motion blur or consistent exposures during long flights. Sadly, the Air 3 doesn’t have a variable aperture, which is a big limitation for me. That’s why I rely heavily on ND filters, even though it gets tricky when light changes depending on whether I include the sky or shoot top-down. That’s one of the reasons I’d love to upgrade to the Mavic 3 Pro someday.

Creatively, I focus a lot on finding unique angles that highlight scale and contrast, whether it’s framing a winding trail through a massive landscape or using elevation to show how tiny human elements interact with nature. I’m drawn to clean, intentional compositions where every element has a purpose.

I often plan my shoots around weather and light. I love challenging conditions, wind, fog, or even snow, because they often create the most atmospheric results. That’s when the landscape truly comes alive.

And since I often fly in remote places, I always pre-scout flight paths using satellite maps and check wind predictions carefully. Yes, drones can handle a lot, but they do have limits. Being prepared allows me to focus on composition once I’m in the air.

I also often shoot panoramas, but never using the automatic panorama mode. The auto function tends to bend images in ways that are difficult to correct, and it gives you very little control over what exactly gets captured. Stitching these auto-panorama shots in Lightroom can be frustrating and unreliable. Instead, I prefer shooting bracketed panoramas manually. That way I know exactly what I'm capturing, maintain consistent exposure across frames, and can stitch everything together properly in post with full creative control. It takes more effort, but the results are worth it.

7. Higher vantage points, whether from a drone, mountain peak, or lookout, change how we see the world. How do you approach composition differently when looking down from above?

My approach to composition doesn’t really change between ground or air, it’s more about adapting to constraints.

The biggest difference is time. On the ground, I can take my time and walk around to refine a composition. In the air, I have 25–30 minutes per battery, so I need to think faster. If I can, I’ll use the first flight to scout, even if I’ve researched beforehand, the landscape always looks different from above.

I try not to repeat the same Instagram-famous angles from known locations. So I explore, and then if I have enough battery or a second flight, I go straight to the most promising shots with intention and purpose.

8. Have you ever encountered unexpected challenges, such as weather changes or equipment issues, while flying in remote regions? How do you prepare or adapt?

Yes, last winter, I was flying in -20°C, and my drone suddenly started an automatic landing mid-flight while passing through a cloud. That was... unexpected 😅 I dropped altitude, got below the clouds, and it stopped panicking. I later read this can happen, so now I’m better prepared.

I’ve been lucky with equipment so far, but I really believe that cold blood and muscle memory are key when things go wrong. That’s why I fly as often as I can, even when I’m not shooting. Practicing basic maneuvers and emergency responses builds the confidence you need when something unexpected happens. For example I’m trying (a key word ;) ) to learn one maneuver which I simply can’t comprehend how to do it. But I will, on some point after hours of training.

“Everyone starts from zero, and trust me, my first few months flying a drone were full of mistakes, frustration, and some very creative swearing under my breath! But if you’re already into photography, aerial work is just another tool to explore your vision in a new dimension. The technical side becomes easier with practice—just fly regularly, even if you’re not shooting anything. Build that muscle memory. You don’t need to be a gamer or a tech wizard to become a good drone pilot.”

9. Your aerial images showcase patterns, light, and scale beautifully. Do you look for certain elements when scouting locations, or do you let the scene reveal itself once you’re in the air?

It’s a bit of both. If I don’t know the place well, I usually start by researching in advance, looking at satellite maps, terrain layers, and sun direction to spot potential patterns or natural contrasts. I’m often drawn to places where textures or lines, like river bends, mountain ridges, valleys, rows of trees, or isolated paths, interact with light in an interesting way.

At the same time, I always stay open to what the landscape reveals once I’m in the air. Some of my favorite shots happened unexpectedly, like a shadow falling perfectly across a field, or a break in the clouds casting dramatic light on a mountain.

The Air 3 gives me the flexibility to quickly change altitude or switch lenses, which allows me to experiment with composition in real time. That balance between planning and improvising is where the real creativity happens for me.

10. What advice would you give to photographers who want to start exploring aerial photography, but might feel a little intimidated by the technology or the legalities?

First of all, don’t be scared. Everyone starts from zero, and trust me, my first few months flying a drone were full of mistakes, frustration, and some very creative swearing under my breath 😅 But if you’re already into photography, aerial work is just another tool to explore your vision in a new dimension. The technical side becomes easier with practice, just fly regularly, even if you’re not shooting anything. Build that muscle memory. You don’t need to be a gamer or a tech wizard to become a good drone pilot.

Start with something simple and affordable. Learn how to control the drone in open, safe spaces before heading into dramatic landscapes. Use auto settings in the beginning if you need to, but slowly move to manual and RAW once you’re comfortable.

As for legalities: yes, the rules can feel overwhelming, but they’re there for a reason. You’re not alone out there, respect for nature and for people is crucial. Do your research. Most countries have drone maps, apps, and agencies that are actually very helpful if you just reach out. If in doubt, ask. It’s better to lose 20 minutes reading than to get fined, get your controller confiscated or, worse, harm someone or damage a fragile environment.

Most importantly, enjoy it. Aerial photography can feel truly magical. You’ll see the world from a completely different perspective, and it opens up a whole new level of creative possibilities. It’s worth the learning curve, I promise.

11. Lastly, where is your next or dream destination to capture aerial shots?

Ah, the list keeps growing! But honestly, I’m still very drawn to Iceland, especially discovering places outside the typical tourist routes, so I don’t think I’ll be venturing too far from there for a while.

That said, we have a family trip coming up in a few weeks, and I’ll be exploring the northwest of Spain. I have a few promising locations in mind, but we’ll see how it goes, I try not to over-plan and let the light and weather guide me.

Madeira and the Azores are also high on my dream list. They still feel a bit out of reach, though. I’d love to spend three or four weeks there, slowly exploring without feeling rushed. But with only 25 vacation days a year, and kids who deserve a real holiday too, it’s hard to combine family time with photography-focused travel. So for now, I usually keep those trips separate.

What else? The usual suspects: Faroe Islands, Greenland, Svalbard, returning to Switzerland in autumn. Maybe one day the U.S. and Canada too. But for now, there’s still so much to discover in Europe, and I’m perfectly happy sticking to this continent a little longer.

Follow Agata’s photography via Instagram here.

Thank you so much Agata for sharing your insights, advice + adventures!